When I enter the studio, the Artist’s face is shrouded in darkness. He’s in the booth, blunt in one hand, 7-Eleven cup in the other. He’s listening to playback of himself rapping over spacey synths and drum patterns that could be confused with howitzer discharge.

He listens to the song and picks up where he left off, freestyling line by line, discarding what he doesn’t need and keeping what he does. Every lyric earns its own accompanying dance move, seemingly composed on the fly but never anything less than casually intricate.

Naturally, the Artist is not alone. On one side is Agoff, a teen of a 20-something with an eraserhead haircut. On the other, King Reefa, a tall, lanky fellow with braids and a deep Tennessee accent. His publicist, tattoo artist, and little brother are also on hand, not doing much of anything. These are his friends and this is his studio session, but the Artist is deeply alone, a Gatsby-figure, holding court in shadowy recording studios, instead of West Egg.

He is king. He is jester. He is too perfect and too strange to exist. His name is Soulja Boy, and he has so much more he would like to give to the world.

I ask the Artist how he views his career. His response is simple. “I’m a legend, man.”

***

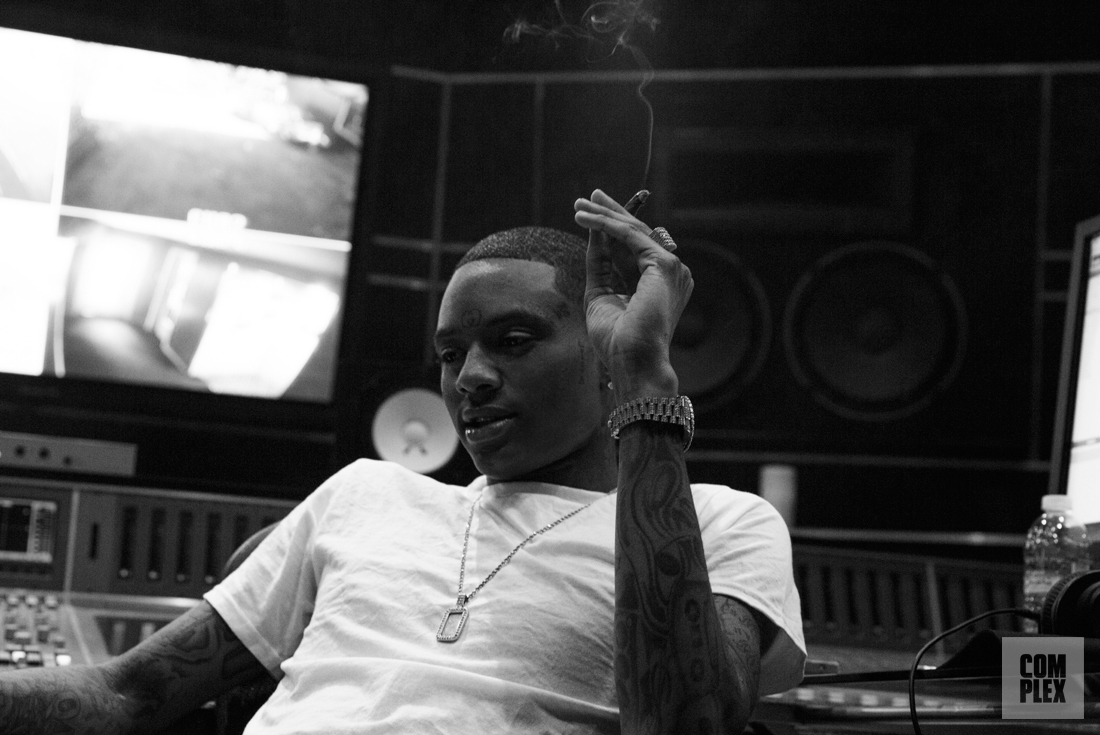

“You ain’t ready for this,” Soulja Boy tells me. He’s wrapped in a tight white t-shirt, elegantly ripped Robin’s Jeans, and a small, tasteful chain. His blunt, thick and taut, resembles a pterodactyl’s leg in a land before man, modernity, and swag. We’re sitting in a Burbank studio, a few blocks from the Disney and Warner Brothers lots. I tell him I was born ready.

“We gon’ start it off like this. Bam!” he says, and begins rattling off his favorite anime films. “Naruto. Cowboy Bebop. Death Note.Full Metal Alchemist. Akira.” In Japan, there’s a word for rabid anime fans: otaku. I am not even a tenth the otaku that Soulja Boy is. “Death Note, that’s my favorite one. You ever seen it?”

“No,” I say, meekly. I’m certain that Soulja Boy is about to be upset with me pretending I was born ready for this. I was in no way, shape, or form ready to talk about anime with Soulja Boy. I have failed myself. More gallingly, I have failed Soulja Boy.

***

Soulja Boy is a genius, and the chief manifestation of his genius is his ability to solve problems that most people don’t even realize they have. He’s naturally intelligent and charismatic, and I have no doubt that if he’d picked up programming instead of music you’d be reading this on a SouljaPhone or SouljaPad right now.

Like any visionary, he’s a charming mixture of hustler and huckster, and for every successful idea he’s had, there have been several that have tanked. A perusal of the past decade in Soulja Boy reveals a roadmap for any musician who wants to make money after the Internet sent the music industry as we know it into a tailspin. One of hip-hop’s greatest trolls, he’s beefed with everyone from the entire U.S. Army to Ice-T, and once claimed to have made his most famous song, “Crank Dat,” in 10 minutes. He worked with Lil B, Odd Future, Chief Keef, Riff Raff, and Migos way before they were big, and he worked with Lil Wayne, Drake, Nicki Minaj, and Andrew W.K. well after they were household names. As we look back at the past decade in rap’s various microgenres—ringtone rap, bop music, cloud rap, trap rap, Vine rap, and perhaps half a dozen others—it seems as if many of them sprang directly forth from Soulja Boy’s ribs. “Every young n—ga that come into the game, you can ask him, ‘Who did this shit first?’ And they’ll say, ‘Soulja boy,” he says. “Period.’”

"I’m a legend, man."

Still, it would be folly not to give Soulja Boy credit as an artist. The music Soulja Boy made during a creatively fertile circa-2010 run of recordings—including his album The DeAndre Way (which he calls “one of my best bodies of art”), the Lil B collaboration Pretty Boy Millionaires, the Young L collaboration Mario and Domo vs. the World, and his solo mixtapes 1Up, The Last Crown, Skate Boy, and Juice—offer an eclectic vision of hip-hop that is alternatively hazy, hard, loose, precise, intentionally blown-out and jagged, or Auto-Tune-drenched and symphonic. Listening to them now, they sound an awful lot like prototypes of the warped hip-hop underground of 2016, as represented by rappers such as Lil Uzi Vert, Lil Yachty, and the Awful Records collective.

But for all that Soulja Boy has given to this world, his genius is far too often only understood in retrospect. When I ask him if he feels like he’s gotten the credit he deserves, he responds immediately: “Hell nah!” Still, he does not care about credit for his innovations as much as he cares about the fact that he’s earned a healthy chunk of change in his career, and that money allows him the freedom to keep innovating. “Everybody’s doing what I was doing 10 years ago,” he tells me. “So I’m worried about the thing they’re all going to be doing 10 years from now.”

***

“Ay y’all, hop off the WiFi!” Soulja Boy tells no one in particular. He’s in the studio, sitting at his MacBook, listening to beats, idly freestyling under his breath. He scrolls, he clicks, he types. He sends emails, he flicks through iTunes, he smokes a blunt that someone else has rolled for him. None of this is particularly interesting on its own, but knowing that Soulja Boy has gotten rich and famous simply by sitting at his computer, performing these basic actions, feels revelatory. Watching Soulja Boy use the Internet is like watching Ron Jeremy’s penis get an erection. “I was always on computers,” he says, adding somewhat cryptically, “ever since I could get on computers.”

“When I was like five or six, I used to play piano,” he says. “I didn’t even know how to read music. I sounded like Beethoven but I didn’t know shit—I just knew what sounded good. If I hit a fucked-up key, I wouldn’t press it no more.” That Soulja Boy, as a child, taught himself to play piano through trial and error should be of surprise to no one: His entire career has been an exercise in throwing anything and everything at the wall and seeing what sticks.

Soulja Boy first rose to prominence in the mid-2000s, a time before the Internet as we know it existed. Perhaps the first web-native rap star, Soulja quickly became a master of using all of the nascent tools at his disposal to turn his art into a brand, then monetize that brand with more flair and less shame than any musician ever, save for perhaps Gene Simmons. “I’ve been using the Internet ever since I made my first song,” he tells me. “Y’all know the rest.”

In case you do not: According to a 2014 Forbes profile, a then-teenaged Soulja would upload his own songs to file sharing services such as LimeWire and Kazaa, ensuring that scores of illegal music pirates would listen to his music by messing with the tracks’ metadata to make it look like they weren’t Soulja Boy songs at all, but instead tracks by famous musicians. He learned to work the systems of such sites as SoundClick and MySpace, where he began to rack up friends at a frenzied pace. “I had 270,000 friends and I was still in the hood,” he says.

In June of 2006, he penned his own Wikipedia page, which promised, “As of now Soulja Boy is sure to land a [record] deal soon.” Though the article was marked by the site’s admins as a candidate for speedy deletion because it did not “credibly indicate the importance or significance of the subject,” it was less than a year later that his single “Crank Dat” became a viral smash, its simple lyrics and complicated dance Supermanning its way into the hearts of mainstream America. In September 2007, the track hit No. 1 on the Billboard Hot 100.

A month later, his debut album, souljaboytellem.com, was released. In addition to “Crank Dat,” it included tracks such as “Sidekick,” which was about T-Mobile Sidekicks; “Bapes,” which was about Bathing Ape clothing; “YAHH,” which was about screaming the word “YAHH” at people; as well as “Donk” and “Booty Meat,” which were both about asses. Though the record eventually went platinum, its existence served as a thorn in the side of the hip-hop establishment.

souljaboytellem.com was released into a world where genre lines were drawn in Sharpie, not the watercolors of today. Few casual music listeners had the varied sonic palette to understand that even if a rap song scans as silly and stupid, its creator could still be extremely savvy and smart. What’s more, the idea of “underground hip-hop” had less to do with the DIY spirit and chaotic pace of artists such as Odd Future, Lil B, and Soulja himself, and more with a strict set of sonic and ideological guidelines, as illustrated by the output of such labels as Def Jux in New York, Stones Throw in Los Angeles, and Rhymesayers in the Twin Cities. This type of underground rap good, even great, it’s just that its practitioners took pains to express their skills, ideologies, and influences in ways that often prohibited the actual music from being particularly enjoyable.

Meanwhile, mainstream hip-hop was dominated by an attitude perhaps best expressed by Mims in his inescapable smash “This Is Why I’m Hot”: This is why I’m hot/I don't gotta rap/I can sell a mill sayin nothin’ on the track. Which is to say: so-called “lyrical” rap was in decline, much to the chagrin of many pillars of the genre, who saw the traditional systems of hip-hop eroding at the hands of catchphrases, easy hooks that could be compressed into bite-sized ringtones, and the Internet. Soulja Boy, with his bright smile, his name written on his glasses in white-out, his album title that was also a website, and his almost punkish disdain for anything beyond the primacy of the beat and the hook, became Public Enemy Number One.

At the age of 17, Soulja faced accusations that he’d ruined hip-hop, as if he was the first person to ever make frivolous rap tracks, or as if hip-hop’s foundation was so tenuous that even the breeze created by the flutter of millions of teens cranking dat might reduce it to rubble. In this way, he is a Christlike figure for Internet rappers: he suffered so that those who came after him might be free to follow their own singular muses, unbound to such archaic constraints as song structure and lyricism in service of a greater artistic vision.

***

These days it’s clear that Soulja Boy never had anything to apologize for. But regardless, he would like to correct the misconception that he’s not a very good rapper, both to the world through his musical output, as well as to me, right here, at this very moment.

“I can really freestyle, man,” he says to me, before playing a thundering, self-produced beat over the studio speakers. It sounds like some unexpected midpoint halfway between Lil Wayne’s “A Milli” and Run-DMC’s “My Adidas.” As I look up from writing a note into my phone, I see Soulja Boy’s face inches from mine, grinning like a maniac as he nods his head in time with the beat. He freestyles for five minutes, incorporating my name as well as objects in the studio into his rhymes as a way to prove he’s not just rapping a pre-written verse, periodically putting his hand on my shoulder as if to focus my attention on him and him alone.

And so, I would like to take this moment to say that I have seen Soulja Boy freestyle, and it was pretty good. No one is allowed to say he’s a bad rapper ever again.

***

“The rap game fucked up,” Soulja Boy tells me. “People are still trying to sell 10 million albums, but that shit’s over with. But everything’s going to balance out. You just got to give it time.” When Soulja says things like this, he sounds less like a 25-year-old rapper with tattoos on his face and more like a venture capitalist making market projections.

In a sense, the triumph of Soulja Boy is as much a story of business successes as it is one of artistic coups. As the concept of the album fell into disarray and hip-hop’s primary mode of income vanished, Soulja worked to exponentially expand upon the ways in which a rapper could get paid. It’s not that Soulja only did the stuff that no one else was doing. Instead, he did everything, some of which happened to be what no one else was doing.

“You can’t pick what goes viral And I ain’t going to sit around and wait. I just create.”

“I did so much stuff bro,” he says, and he means it. Stuff like rapping phone numbers in songs, and rigging it so when you called the number in that song, you would hear an ad. This is a real thing that Soulja Boy Did, in on his inescapable hit “Kiss Me Thru the Phone.” “I was getting checks for three years straight,” he says of the ploy, which he claims at one point was netting him $50,000 a month. Throughout the years he’s also hawked hoverboards (to disastrous effect), created a short-lived animated series about himself co-starring the guy who played Carlton from Fresh Prince of Bel-Air, and even charged people money to have him follow them on Twitter.

Then there was Soulja Boy: The Movie, a direct-to-DVD documentary about Soulja Boy directed by the Oscar-nominated filmmaker Peter Spirer. It is a deeply strange and mesmerizing film, showcasing the build-up to Soulja’s criminally underrated third album, The DeAndre Way. In the film, Soulja moonwalks on a pile of cash, jumps fully clothed into a bathtub of water, sports a chain with a piece that is also a diamond-encrusted remote-controlled car, gets robbed by someone on his own label, and has a falling-out with his best friend Arab. It is narrated entirely through YouTube comments. I don’t think I could give any context to this stuff if I tried, as the movie works best as a jumble of unpredictable moments, and is best consumed while heroically stoned. When I bring the film up to him, he asks what I think of it.

“I think it’s amazing,” I say.

“Swag,” he responds.

***

These days, Soulja’s extramusical hustles are plentiful still. He is currently the purveyor of light-up shoes called SBeezy Lights, runs a line of hookah pens, and owns a stake in the well-known streetwear brand BLVD Supply. On top of that, he is a subject of VH1’s Love and Hip-Hop, though he says he’s looking to parlay his renown as a highlight of the show’s ensemble cast into getting his own series. He’s also working on new music with SODMG, always doing shows, still producing beats for other artists, and still hunting out new talent and new sounds—he recently worked with ascendant Atlanta upstart Lil Yachty to release “Snapchat.”

Earlier this week Soulja released an album, titled Stacks on Deck. Its cover features Soulja sitting on a gargantuan pile of money. It features the track I watched him record, now titled “Benihana.” Its hook goes, “I’m back in the kitchen huh, still water whippin’ huh,” and in its own way, it expresses what seems to be the governing philosophy of Soulja Boy: That if you keep making stuff, eventually some of that stuff will stick. It’s less of an exercise in innate brilliance, and more of a testament to the power of constant grinding, living proof that there’s some truth to the adage, the harder I work, the luckier I get.

“I don’t give a fuck if I don’t sell another album,” Soulja says. “Something’s gonna pop. Some money’s gonna be made.”

Still, Soulja Boy understands that this type of hustling only works if there’s something behind it backing it up. In order to make money off of music even in unconventional ways, there has to some smattering of brilliance, intelligence, talent, authenticity—or at least a quality product—shining through.

So Soulja Boy keeps rapping, keeps releasing music at a frantic pace, knowing that eventually he will hit paydirt and release something that reminds the world why they fell in love with him in the first place. “You can’t pick what goes viral,” he says, “And I ain’t going to sit around and wait. I just create.”