House Music History

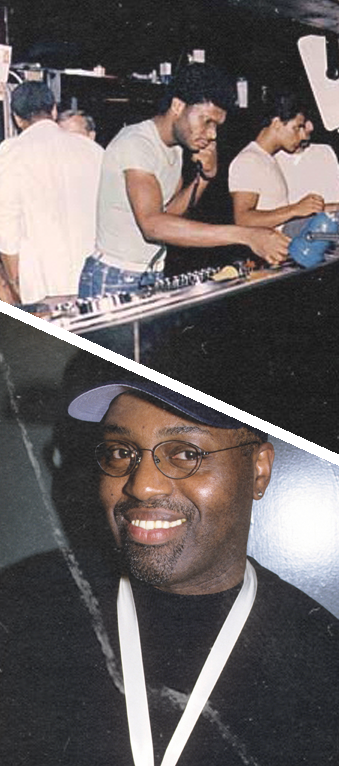

When a young Bette Midler left the stage at the Continental Baths in the early 1970s, two black teenage disc jockeys named Larry Levan and Frankie Knuckles commanded the DJ booth.

Levan’s mixes gained renown for blending bits of progressive rock, soul, and rhythm and blues alongside standard disco fare. By 1977, he was a resident spinner at the Gallery, a well-regarded disco space located at 132 West 22nd St. in Manhattan. When asked to take the helm as the lead resident at a new underground garage-turned-night spot, the Paradise Garage, Levan jumped at the opportunity. It gave him a chance to play his sound, unrestricted, on a loud and custom-designed sound system to a crowd of regular followers that numbered in the thousands.

Similar to his childhood friend Levan, Knuckles’ popularity in New York exploded during the disco era while he was a resident at the Gallery. In fact, he became so popular that when a group of Chicago-based promoters were opening a new club called the Warehouse, they reached out to Knuckles to spin at their new space. Not intimidated by the challenge, Knuckles accepted, splitting the New York-based dance legacy between two separate cities.

By the end of the disco era it became commonplace for labels to tap DJs to create longer, break-laden dance remixes. By the late ’70s/early ’80s, the dance remix was a concept unto itself, and when Knuckles took tracks like Michael Jackson’s 1979 hit “Rock With You” and made remixes, magic happened. Using drum machines to replace live drumming on soulful disco classics and laying sweeping, drawn-out melodies on top created such a distinct sound that Knuckles’ residence at the Warehouse quickly became seen as one of the best. In fact, the spot was so beloved that Chicago dance fanatics and global crate diggers alike started to ask record store owners about the music that they heard “at the Warehouse.” Over time, people dropped the “ware” and simply came in search of “house” music.

While Knuckles transformed original house tunes like Jamie Principle’s 1982 single “Your Love” and remixes of disco-era tunes like First Choice’s “Let No Man Put Asunder” into instant “house” classics, Levan played from midnight on Saturday through Sunday afternoon at the Paradise Garage. Levan’s ability to create a binding tie between soul and dance may not have been “house music” per se, but when influential tastemakers took notice, his progressive sets certainly whet America’s appetite for the style of music that Knuckles was using to dominate the Windy City.

Legendary DJ/remixer Francois Kevorkian tells Rolling Stone that “[Levan’s mixes were] kind of hard to characterize. He could just as well be playing some Fela Kuti and Ginger Baker or he could playing [sic] some rock music. Pat Benatar. Even in those early years, he was favoring a great variety of things, some of which he was pretty faithfully carrying on the legacy of an entire generation of musicians, like old people from Philadelphia, like Teddy Pendergrass and the Jones Girls and so on and so forth.”

On July 7, 1983, Factory Records artists New Order performed at the Paradise Garage. New Order was assembled from the remnants of Manchester-based post-punk band Joy Division. Upon returning to the U.K., the group took what they loved about American house from touring in New York and turned it into huge business. In deciding to create a “Hacienda” back in the U.K., New Order started a revolution that eclipsed the 1970s era’s four-on-the-floor standard. That “Hacienda” ended up being a famed and influential warehouse-turned-nightclub open in Manchester from 1982 to 1997.

However, it was Chicago house music that made its way to the U.K. first. DJ/producers like Farley “Jackmaster” Funk, Steve “Silk” Hurley, and Marshall Jefferson were initially successful without American support. Songs like the aforementioned Funk’s “Turn Your Love Around” and Steve “Silk” Hurley’s influential “Jack Your Body” soon surged to the top of the U.K. pop charts. In 1987, the Chicago-based quartet of Knuckles, Marshall Jefferson, Fingers, Inc., and Adonis toured England for the DJ International Tour.

A few months prior, a sextet of soulful house-and-funk-break-adoring U.K. DJs celebrated Paul Oakenfold’s birthday on the Spanish isle of Ibiza. A trip to the island exposed the six DJs to a sound they were unfamiliar with, while partying at the legendary Amnesia nightclub. Instead of tracks bearing a similar style to funky stompers, the sound they were introduced to was acid house: a wild, squelching, and frenetic-beating electronic thing all its own, imported from contemporaries in Chicago.

Although techno doesn’t factor heavily in this particular history, the inception of acid house is a moment to “put your hands up for Detroit.” Detroit techno progenitor Derrick May confirms that he once sold a Roland TB-303 electronic synthesizer to Knuckles in the early 1980s. While Knuckles isn’t credited with creating what became acid house, the 303’s influence continued its migration from the Motor City to Chi-town. The sound pushed those on the dance floor to want to dance harder and longer, the desire to “jack” one’s body (torsos moving forward and backward in a rippling motion) then becoming popular in the club scene.

Acid house's minimalist style blended house’s thumping drum machine kicks with electronic squelches via the Roland TB-303 electronic synthesizer-sequencer, having its frequency both under- and over-modulated. DJ Pierre and Phuture’s “Acid Tracks” was the first big hit of the sound, being championed by Chicago DJ Ron Hardy.

In the hands of Spaniards and their isle of globetrotting party friends, acid house created a euphoric atmosphere that reintroduced the 1970s era of Northern England’s Northern Soul dance parties. Both scenes were surprisingly peaceful and well-known for their raucous late-night events and were championed by DJs like Oakenfold. Acid house and its associated cousin, rave culture, would come to dominate first England, then the world.

Meanwhile, back in America, house music was an underground phenomenon occasionally peeking its head onto the Billboard charts through U.K. to U.S. crossover hits. In 1988, English house acts A.R. Kane and Colourbox paired with fellow Englanders and house DJs Chris “C.J.” Mackintosh and Dave Dorrell to form a one-off recording act called MARRS and put out “Pump Up the Volume.” The track blended snatches of Eric B. and Rakim’s 1987 rap hit “I Know You Got Soul,” the trailer of 1968 B-film Mars Needs Women, and 27 other breaks from b-boy lore to create a No. 1 single that appropriately encompassed everything from the Continental Baths to the Hacienda and beyond. The presence of rap in so many U.K. house tracks was intriguing, but it wasn’t until Native Tongues-affiliated rap trio the Jungle Brothers got involved with 1988 single “I’ll House You” that the unity between rap and house reached another level.

“I’ll House You” wasn’t a major commercial smash but was a hit with critics. The Source gave the album a five-mic rating. The proto-hip-house track sampled New York-based producer Todd Terry’s “Can You Party” (recorded under the name Royal House), Chicago producer Marshall Jefferson’s “Move Your Body (the house music anthem),” rap classic “It’s Yours” by T La Rock, and New York post-punk dance act Liquid Liquid’s single “Optimo.” In crystallizing all of the best of American dance and pop influences into one song—and throwing in an African chant-style vocal hook of “Girl, I’ll house you, you in my hut now”—The Jungle Brothers created an iconic cut.

The 1990s were house music’s golden years. Italian heavyweights Black Box released “Everybody Everybody” in 1991. In 1992, Germany’s Snap! achieved global recognition for “Rhythm Is a Dancer.” The following year, American vocalist Robin S. shared “Show Me Love” with the world, only to watch it become a timeless dance floor smash. By 1996, the Bayside Boys’ house remix of Los Del Rio’s instructional dance anthem “Macarena” spent 14 weeks at the top of the American charts. House had officially eclipsed the underground and entered its first era of all-encompassing pop dominance.

Regarding what was to come next, Simon Reynolds’ Energy Flash, published in 1998, states the following: “With their jagged edges and lo-fi grit, [Terry’s] cut-and-paste tracks were a world away from garage and house’s polished production and smooth plateau of pleasure. Terry used funky breakbeats and jittery electro beat-box rhythms as well as house’s four-on-the-floor kick drum. Terry’s sound was hip house, a hybrid genre that was a fusion of house and rap.”

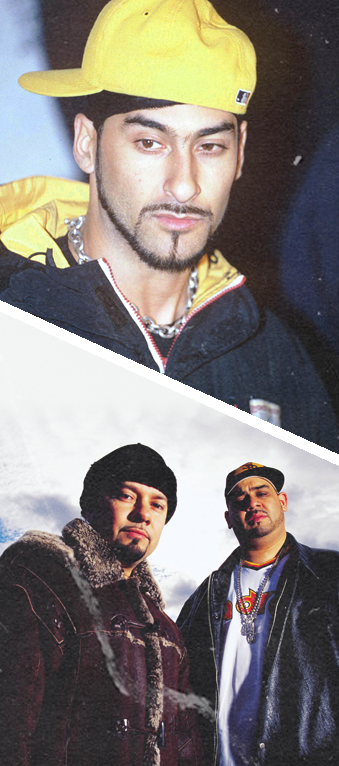

Between 1990 and 1994, while house was a dominant mainstream sound, the underground again proved vibrant drivers of innovation in the genre. DJs like Terry and Armand van Helden were spinning hip-hop and Italo disco at underground parties in the Big Apple and U.K.-friendly house, hip-hop, and soul at Boston’s Loft nightclub, respectively. New Jersey boasted clubs like Newark’s Zanzibar where DJ Tony Humphries reigned supreme. Also key was New York’s Latin scene with the tandem rise of Kenny “Dope” Gonzalez and “Little” Louie Vega as Masters At Work. New York City-based Puerto Rican performers like TKA had breakout success with “Louder Than Love.”

In 1993, the aforementioned Van Helden moved from Boston to New York City. “I didn’t see my future expanding,” he told Red Bull Music Academy. “A lot of dark things started happening on a personal level, and I had been to New York a number of times by that point. Boston is a great appetizer for New York, but it’s only so big. I had to go.” Regarding meeting the likes of Terry and other prominent NYC DJ/producers, Van Helden said, “They’re all cool with me now, but it was very hard for anybody outside at any circle, at any level—U.K. guys, Jersey guys—you just couldn’t break that clique,” he said. “But you wanted to be in [the clique with producers like Terry] because that was it.”

In August 1994, Atlantic Records asked Terry to remix U.K.-based duo Everything But the Girl’s “Missing.” He obliged. In giving Tracey Thorn’s vocals room to breathe on top of the original’s ambient feel and adding a heavy, funky, and soulful bass line, he crafted an instant classic and No. 1 single on Billboard’s Mainstream Top 40 Chart. For Terry, this marked his decided crossover from the underground music world to the global stage. Soon thereafter, Van Helden—the “uncool” producer from Boston trying to fit in—would get his chance to shine with a similar break.

The idea that Van Helden, now best known for pairing with A-Trak as disco-boogie-meets-electro-house tandem Duck Sauce, was an outsider is almost unbelievable, but true. By 1994 he was working his way into house music’s inner clique by making waves with popular dance releases like “Witch Doktor” released on Strictly Rhythm. In July 1996, Atlantic Records reached out to the DJ/producer to remix Tori Amos’ single “Professional Widow.” The final product was an enormous record that reached No. 1 on the U.K. pop chart and No. 1 on the U.S. dance chart, too.

Much like house music’s migration overseas in the 1980s, a new set of names in the U.K. started taking notes from the Chicago/New York City hybrid sound. In 1997, French producer Thomas Bangalter paired up with his friend Guy Manuel de-Homem Christo and released Homework, an album from their prog/punk-meets-rap-meets-acid-house band Daft Punk. Homework’s first two singles—“Da Funk” and “Around the World”—emerged as No. 1 American club singles, too.

Daft Punk’s longtime manager, Pedro “Busy P” Winter, told Pitchfork that he and Daft Punk “belong to the Generation ’75.” “We were born in 1975, so we are somewhat in the middle of the rebellion and freedom of the ’70s and the consumer culture of the ’80s,” he said. “Maybe because of that, marketing and communication were always a part of what we did. Daft Punk didn’t want someone with experience in the music business as their manager; they wanted someone with lots of energy who was the same age as them and had the same interests.”

Daft Punk’s second album, Discovery, saw their filter-filled disco/funk become more pronounced. Thick pop-punk drums came into the picture, and the duo solidified a lasting signature sound. Mixmag voted “One More Time” as the greatest dance record of all time, 13 years after its release. In crystallizing the influences of America’s reclamation of dance from Europe and remembering the historical influence of disco and soul records on the sound, it—like the Jungle Brothers’ “I’ll House You” some 12 years prior—again set a new standard for house music.

In 2001, following the breakout success of “One More Time,” Bangalter told DJ Times about house music that, “has gone from nothing to an underground [culture] to a subculture to a bigger culture, which is still alternative in some way, as compared to Europe where it’s like what hip-hop or R&B means in America—which is a great thing because for music, this is what we have been fighting for. But the thing that still drives you is trying to have people accept new things.”

Between 1999 and 2010, house music truly became a worldwide phenomenon. German hard electro band Zombie Nation’s heavy techno and hard house inspired “Kernkraft 400” was a surprise crossover hit in 1999 and is still a staple of sports arenas worldwide. In the U.S. and worldwide, house-music-based club and festival culture became a million-dollar industry. Labels like Ultra Records exploded in popularity. Moby successfully licensed all of the tracks from his 1999 album, Play, for commercial use. By the middle of the decade, when the Internet became more prevalent than ever before and created a wireless link that again turned the world into an interconnected mass, house music was primed to prosper.

Starting in 2005, three concurrent movements around the globe would come to define house at present. In North America, Wesley Pentz was a Tupelo, Miss.-born DJ/blogger/record collector who went by the name Diplo (short for diplodocus, a long-necked dinosaur that roamed Earth in the Kimmeridgian age). From 2004 to 2007, Sonny Moore was the lead singer of pop-punk act From First to Last and just three years away from severe vocal issues that would cut short his ascent to mainstream rock stardom. Just north of the border, there was Toronto-based Internet message board fanatic-turned-bedroom-electro-house producer Joel Zimmerman, who under his message board handle of “Deadmau5” (and a giant glowing mouse head mask) became an almost instantaneous global phenomenon.

In France, Daft Punk’s former manager Winter had yet again stumbled upon a duo as inspired by rock as they were dance. Xavier de Rosnay and Gaspard Augé’s project became known as Justice. The duo gained steam as they prepared tracks for a possible entry into the French qualifier for the ABBA-to-Conchita-Wurst famed Eurovision competition.

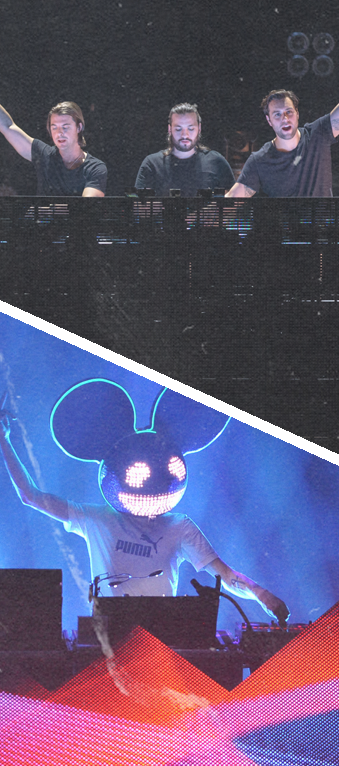

In Sweden, Sven Axel Christofer Hedfors (a.k.a. Axwell) and Sebastian Ingrosso were respectively a trance-loving dance producer and rave enthusiast-turned-house DJ/producer. Steve Angello was emerging as a funk-driven house DJ and production superstar on the same level as the likes of Armand Van Helden just a decade prior.

Diplo’s career was built on the back of his love of the Southern rap records that supplanted house music on the American Billboard charts in the 2000s, as well as a record collector’s love of great music from all genres. By the mid-2000s, his underground “Hollertronix” parties thrown in an abandoned mausoleum in his his then-home of Philadelphia were so critically acclaimed that he, his friends, and associates started the Mad Decent label to release remixes and tracks that were popular at the party. From club-ready tracks fusing Baltimore’s house music scene to drum breaks from James Brown funk hits and electro disco B-sides, the label initially made very little money, but it created a community of dedicated followers that existed almost entirely on the Internet. In inspiring others like Montreal-based teenage DMC champion Alain Macklowitz to create labels like Fool’s Gold, Diplo was a groundbreaker.

In 2004, Diplo told Stylus Magazine that his style was best-defined as an attempt to “be open-minded, pushing new music and pushing shit that’s out there…. Try to take some reasonable things and push it a little bit to the mainstream, what I can get my hands on.” This meant everything from Brazilian baile funk to Dirty South rap, dancehall, Dominican dembow, electro house, and much more in the past decade.

In France, the concurrent trends of Daft Punk’s rock chords and sweeping, ethereal melodies allowed Justice to break out with their 2006 collaboration with Simian Mobile Disco, “We Are Your Friends.” Continuing into 2007, their † album featuring “D.A.N.C.E,” stands as a contemporary touchstone recording of modern house music.

House’s influence spreading to Sweden in 2005 involves names like Steve Angello and Eric Prydz breaking out as global hitmakers by 2008. Angello’s remix of Robin S.’s 1993 hit single “Show Me Love,” alongside Dutchman Laidback Luke and Prydz’s sexy and swinging house tracks like 2004’s “Call on Me” and 2008’s “Pjanoo,” firmly established Sweden as an emergent powerhouse locale in house music. Angello teamed up with fellow Swedes Ingrosso and Axwell to become Swedish House Mafia. They tapped rapper/producer/pop star Pharrell to join them for their 2010 single “One.” By then, blending rap and house to make a hit had become a tradition with a 25-year history of success. Sure enough, the song was a superstar-making turn for all three DJ/producers.

By 2010, Moore took his Myspace-era fame from From First to Last and began producing electro house tracks as “Skrillex.” Gaining notoriety in Los Angeles’ club scene, Deadmau5 released Skrillex’s Scary Monsters and Nice Sprites EP. Skrillex’s sound blended elements of post-punk edginess and a wobbling-bass line variation on Croydon, England-developed dubstep, a genre created as a direct and underground answer to mainstream-ready dance. More dub-reggae than disco, Scary Monsters and Nice Sprites became a surprise entry and fast-riser on the Billboard 200 album charts, despite no radio play or mainstream marketing. Skrillex became a self-made star.

References.

- Herbers, John. "BLACK POVERTY SPREADS IN 50 BIGGEST U.S. CITIES." The New York Times. January 25, 1987. Accessed December 12, 2015. http://www.nytimes.com/1987/01/26/us/black-poverty-spreads-in-50-biggest-us-cities.html.